Reference of the document

Walker, A.M., Albizzati, P.F., Milios, L., Piñero Mira, P., Besler, M. et al., Capturing the Potential of the Circular Economy Transition in Energy-Intensive Industries - Summary Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2025, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/4604362

Summary of the main ideas and results

Circular Econonmy (CE) aims to reduce the use of primary resources by:

-

designing products to be resource-efficient and longer-lasting and by

-

maintaining and recirculating the value and the materials that make up these products at the end of their life.

This also reduces the need for additional energy and primary resource extraction.

This study focuses on the steel, aluminium, cement and concrete, and plastics industries. These sectors are energy-intensive, large Greenhouse Gases (GHG) emitters and significant environmental polluters. Together they account for approximately 44% of the EU’s GHG emissions from manufacturing and contribute significantly to air pollution, increasing levels of particulate matter, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides emissions. However, they also provide the building blocks for a wide range of strategic downstream industries and are enabling for the EU’s autonomy and competitiveness. In addition to a total turnover of EUR 729 billion and direct employment of about 2.4 million full-time equivalent (FTE) persons, these sectors have a substantial multiplier effect in terms of Gross Value Added (GVA) and job creation downstream

The implementation of Circular Economy (CE) strategies in the European Union presents significant potential for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, decreasing fossil fuel use, and altering trade dynamics. CE strategies related to material reduction, reuse and recovery complement industrial decarbonisation measures and have the potential to double GHG savings of energy-intensive sectors by 2050.

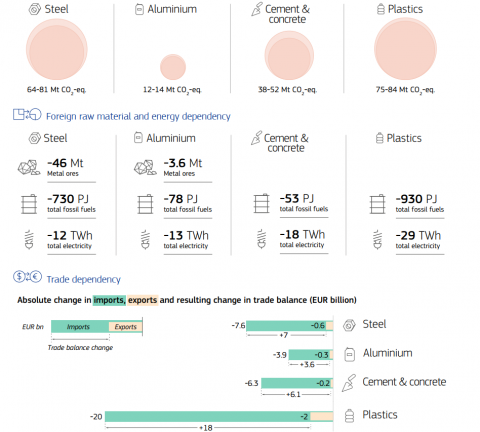

Through a multi-method analysis, this study shows that an ambitious CE scenario can yield substantial annual GHG savings, with annual emission reductions of 64-81 Mt CO2-eq. in steel, 12-14 Mt CO2-eq. in aluminium, 38-52 Mt CO2-eq. in cement and concrete, and 75-84 Mt CO2-eq. in plastics by 2050. The total value (189 to 231 Mt CO2-eq. / year) is roughly in line with the earlier estimates (300 Mt CO2-eq. / year) by Material Economics that we reported upon earlier.

Morover, the implemented CE strategies mainly decrease EU imports, reducing trade dependency and increasing the trade balance by over EUR 30 billion/ year compared to the decarbonised baseline.

The study underscores the importance of creating conducive framework conditions to support CE integration in hard-to-abate industries in the form of a policy mix. Policy recommendations include:

-

promoting recycling technologies to improve recyclate quality,

-

reducing material input through more efficient design, and

-

mandating Green Public Procurement to create market demand for more circular material use.

These strategies align with EU goals to enhance sustainability and competitiveness, while mitigating macroeconomic risks from global dependencies.

What did we find interesting in this document?

This document claims to be the first to use a unified methodology to assess the environmental, economic and social effects of the implementation of Circular Economy strategies in the EU, across a broad set of energy-intenstive sectors, which are notorious for being those where GHG emissions are "hard to abate".

The overall message regarding the impacts of Circular Economy for the European Union is positive along almost all indicators:

-

GHG emissions and the consumption of other primary resources (metal ores, fossil fuels, electric energy) are strongly reduced compared to a reference scenario with a strong decarbonation;

-

the trade balance is massively improved;

-

the drop in the Gross Value Added (GVA) of the respective sectors is between 9 and 26 times smaller than the one in GHG emissions, which shows a strong decoupling between economic activity and material consumption: material consumption is strongly reduced, but economic activity is hardly affected.

What is it in this document that we disagree with or find disappointing?

The document is rigorous, because it considers that Circular Economy measures are implemented in complement to a reference scenario in which these sectors are massively decarbonised. This results in reductions in GHG emissions due to Circular Economy measures that are low, because the reference scenario already displays low GHG emissions. In addition, the document does not compare the situation in 2050 with Circular Economy and decarbonisation to a Business-as-usual scenario with neither Circular Economy nor decarbonisation. It would have been interesting to show a graph with the two dimensions:

-

the reduction in the quantities of basic metal, material or chemical being consumed, because of Circular Economy mreasures;

-

the reduction in the GHG emissions per tonne of basic metal, material or chemical consumed, itself split between the effects of: (a) substitution of primary by secondary (= recycled) metal, material or chemical, because of Circular Economy measures and (b) of decarbonation of the production process for primary metals, materials or chemicals.

Such a graph would have helped better assess the climate benefits of Circular Economy. The same could have been done for all other categories of environmental impacts (water use, ecotoxicity, etc).

Similarly, the document does not compute the economic savings in investment in the electric system and in the decarbonised manufacturing processes that are induced by the reduction in consumption of basic metals, materials and chemicals induced by Circular Economy measures. We find this regrettable.